Author: Shinimas

Remember when microtransactions were purely free-to-play and was considered a terrible bad manners to have them in a subscription game? I remember. It seems like it was an eternity ago. But today, the reality is that microtransactions are present in almost every game, regardless of other aspects of its business model. The developers have learned to masterfully implement additional payments, dancing on the fine line between the maximum possible profit and player dissatisfaction. However, sometimes they do overstep this line, and then everyone, except for users with the thickest wallets or the most brainwashed, begin to grumble. So where is this barrier that developers shouldn’t cross?

Macro transactions

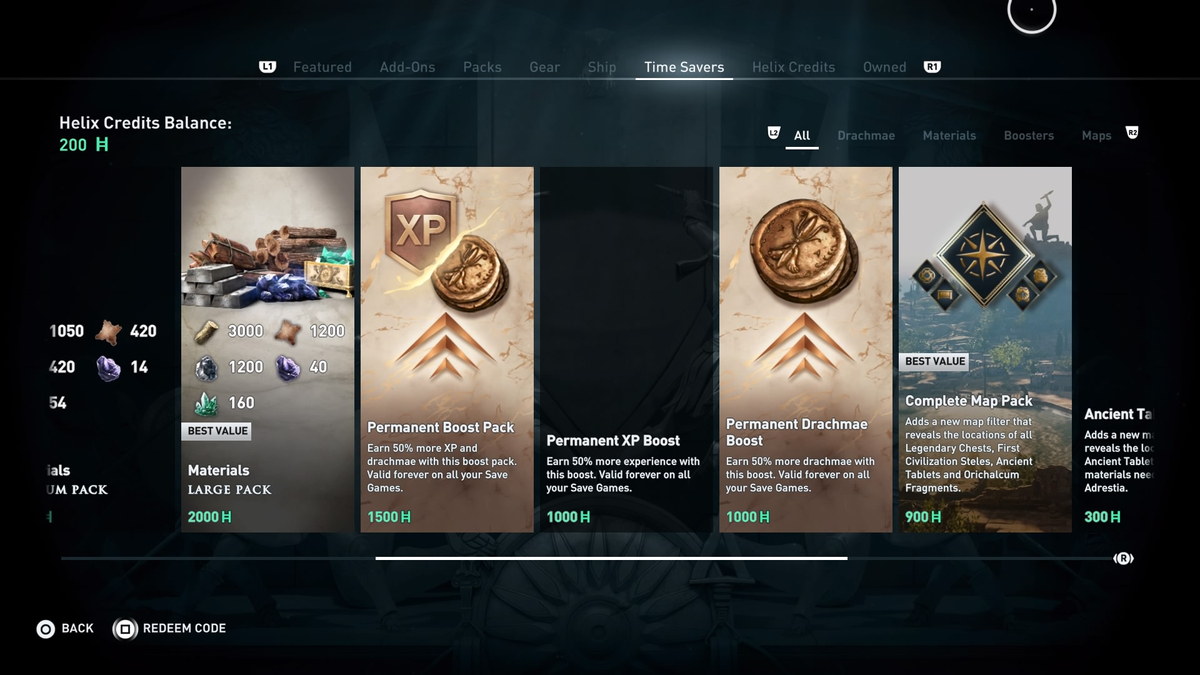

The most obvious example of the microtransaction kink is the price tag. If the developers ask a couple of bucks for a service or any item, then this is unlikely to cause outrage in someone. However, when prices reach several thousand rubles, it seems that the developers live on another planet. In reality, such positions are designed for the so-called “whales”. This is how microtransaction specialists call customers who are ready to buy everything, regardless of cost. At the same time, whales can be not only rich players, but also hardcore enthusiasts, or people with an unhealthy attachment to their hobbies.

You have to pay for all the good

Microtransactions tend to generate much higher returns than game box or subscription sales. Of course, developers begin to prioritize this monetization model and adjust their product to it. Let’s say the artists have painted a great set of armor. Obviously, marketers will insist that you can purchase it exclusively for an additional fee, and “for free” in the game you can knock out something simpler. Everything is not limited to cosmetics alone. In the store, you can sell all kinds of items for the convenience of the game. If the store sells, for example, an expansion of the size of the inventory, then the cunning developers will make the basic inventory smaller, and the mobs in their game will throw garbage that will clog bags in order to encourage the player to fork out quickly. Basically, instead of making the game as good as possible, the developers try to invent problems for the players in order to then sell them their solution. The notorious invisible hand of the market and the principle “if you don’t want to – don’t buy” in this case completely ceases to work for the benefit of the consumer.

Fantasy and reality

The dominance of microtransactions can turn into a big problem, too. We play games to relax and unwind from pressing problems. When we are poked in the face with dollar-sign advertisements at every corner, the feeling of immersion in the gameplay diminishes, if not completely disappears.

The main goal of game makers ten years ago was to create the most exciting product that players will want to return to from month to month. When marketers begin to drive game design, as is so often the case, the direction of the game changes dramatically. In the first place are psychological tricks and tricks designed to get into the player’s head and shake out as much money as possible. This approach does not fit in any way with the idea of a hobby, which should be a pleasant leisure.

“Innocuous” microtransactions

Are there any advantages to microtransactions? In theory, they exist. If developers can count on additional profits from new cosmetic items, then they have the opportunity to expand the art department. In this case, new employees will work on skins for the store, while the rest will continue to rivet items for the base game. As a result, we do not lose anything and we get the opportunity to buy the outfit we like in the shop, which otherwise simply would not exist. However, this is all theory, and how much it corresponds to practice is a big question.

Another useful microtransaction is payments for services, which cost developers additional funds. For example, slots for new characters in theory can have an impact on the cost of storage, so it is quite reasonable that you have to pay for them.

The price tag as a limiter also has a certain meaning. The ability to transfer a character from one server to another creates the risk of imbalance in the population, when one server is empty, and the other begins to choke from an overabundance of users. If you have to pay for resettlement, then this naturally limits this process.

How many microtransactions in the game do you consider acceptable, or are you rejected by the very fact of having them? Are you able to put up with some types of payments and do you have some red lines that a developer should never cross?